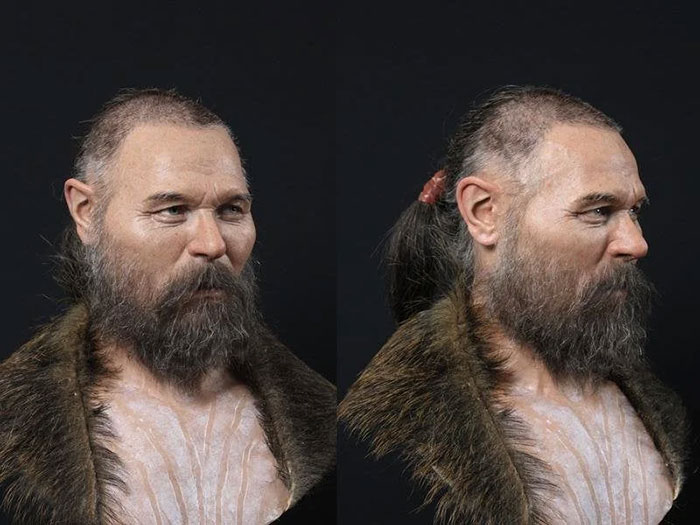

A forensic artist used 3-D scans of the hunter-gatherer’s cranium whose skull was mounted on a stake 8,000 years ago to envision what he may have looked like in life.

Swedish archaeologists made a rare discovery in 2011 when they found human skulls mounted on stakes at an ancient burial site dating back 8,000 years.

Through the remarkable feat of computer-aided facial reconstruction, a talented forensic artist named Oscar Nilsson successfully brought one of these skulls to life.

Using clues from archaeology and genetics, Nilsson created an accurate portrait of the Mesolithic Cro-Magnon man (Ludvig), whose head had been mounted on a wooden stake after his death.

The newfound ability of AI facial reconstruction now allows us to envision this mysterious Cro-Magnon with his distinct features, such as a long head, prominent cheekbones, blue eyes, and light brown/blond hair.

The excavation site at Kanaljorden in Motala, Sweden, where the skulls were discovered, presented an unusual arrangement of remains, including animal bones, on a stone platform submerged in a small lake.

The presence of wooden stakes within two of the skulls intrigued researchers. Nilsson’s facial reconstruction, which involved scanning Ludvig’s skull and creating a 3-D replica, was a challenging endeavor due to missing jawbones and limited information.

However, the recreation offers insights into Ludvig’s pale complexion, hair color, and eye color, shedding light on the life and appearance of this ancient individual.

While Ludvig’s exact cause of death remains unknown, the facial reconstruction reveals a one-inch healed wound on the top of his skull.

The burial site exhibited distinctive trauma patterns, with females showing injuries on the back and right side of the head, while males suffered a single blow to the top.

The discovery raises questions about the society’s treatment of the injured individuals, as they appeared to have received care and healing.

The reason for mounting Ludvig’s skull on a wooden stake remains unclear, as the Mesolithic people generally respected the bodily integrity of the deceased, and decapitation as a punishment emerged later in history.

The mounting of two crania on stakes suggests that they were displayed, possibly in the lake or elsewhere, serving as a form of exhibition or deterrent.

The archaeological evidence at Kanaljorden did not directly indicate decapitation or forced removal of jaws from the buried individuals, leading to speculation that such actions may have occurred after significant decomposition or in the context of another burial.

Nilsson hopes that his facial reconstruction not only deepens our connection to history and archaeology but also showcases the power of science in resurrecting the past with intimate details.

Theodore Lee is the editor of Caveman Circus. He strives for self-improvement in all areas of his life, except his candy consumption, where he remains a champion gummy worm enthusiast. When not writing about mindfulness or living in integrity, you can find him hiding giant bags of sour patch kids under the bed.